Blog post #6 Towards New Worlds MIMA, Middlesbrough

By Louise Atkinson and Grace Joseph

- This blog post focuses on a visit to MIMA in Middlesbrough to see Towards New Worlds, an exhibition showcasing disabled, Deaf, and neurodivergent artists.

- The show featured interactive sound sculptures, video works, and installations.

- Themes of access, the senses, and lived experience were central. Artists used sound, touch, and writing to invite new ways of understanding art and disability.

- The visit inspired reflections on making contemporary art more inclusive and multisensory.

On Friday 7th February, Artist-in-Residence Louise and Grace, the Arts Stream Research Associate, visited Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art (MIMA), just in time to see the Towards New Worlds exhibition before it closed. Towards New Worlds is a ‘large-scale exhibition sharing fifteen artists’ experiences of seeing, hearing, feeling and sensing the contemporary world’ curated by Helen Welford and Aidan Moesby (). All of the artists featured in the exhibition are disabled, Deaf, and/or neurodivergent. Helen generously gave us a tour of the exhibition, introducing us to the works on display and explaining the artists’ motivations and the curatorial processes involved. We learned about how artists were commissioned and how sensory and accessible elements played a central role in the curatorial decisions.

Upon entering the exhibition, we were met by four mid-height sound sculptures by Aaron McPeake. These sculptures, entitled Same Same but Different, are cast in the shape of bells and rings and hung from wooden frames, accompanied by handmade mallets. Visitors can strike the sculptures to produce different tones, adding a tactile and sonic experience. The bells invite playful interaction rarely seen in gallery settings. We spoke with Helen about how, even with explicit invitation, touch often feels boundary-crossing in a gallery context. We’ve also been thinking about how audio description and exhibition notes can gesture towards an artwork’s tactility—giving a sense of how an artwork might feel—and offer a more holistically embodied experience. Projects like , led by McPeake and Dr Ken Wilder, and , led by Professor Hannah Thompson, for example, are reimagining sensory reception in contemporary art and in museum settings.

A nearby video work, [sound of subtitles] by deaf South Korean artist Seo Hye Lee, shows archive footage of hands throwing clay pots. In this piece, the screen is split into three, each section showing a version of the same silent imagery but with varied subtitles: some literally descriptive; some poetic, gesturing to a sonic experience beyond or within the visual; and some describing an imagined musicality. Across the same three moving images, for example, there is ‘[shaping]’, ‘[sound of an empty room]’, and ‘[mysterious string music]’. Of this piece, Seo Hye Lee writes: ‘Regardless of hearing ability, one can explore their own unique soundscape and reimagine the meaning of listening’ (). Along the tops of the surrounding walls, vinyl text excerpts from the video are displayed within square brackets, reinforcing the sensory themes of the exhibition and immersing the viewer.

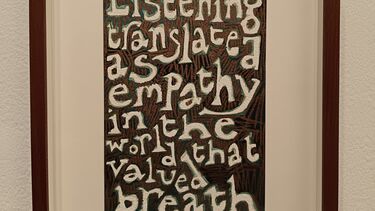

Ideas of displaced and simulated sensation continued into the next room in the video work by Molly Martin, which depicts her standing in a freezing stream. This invokes, we’re told, a sensory state that parallels aspects of Martin’s experience of epilepsy. Opposite, Jade de Montserrat’s work explores fragments of text, by drawing words and playing with the readability of language. The phrases, collected from various sources, are partially obscured, erased, or fragmented, making some words clear while others become unreadable. This created gaps in communication, where meaning was unstable and open to interpretation. We were both drawn to the phrase ‘Listening translated as empathy in the world that valued breath’, both for its ambiguity and for its connection to Cripping Breath. Diverse, embodied experiences of listening; listening as a caring practice; and translation between perceptual modes and value systems are all connected with our thinking about breath.

An installation by Małgorzata Dawidek combines photography, maps, drawing, and small specimen jars, responding to the geology of the Tees Valley. The work explores the relationship between nature and the body, specifically linking the declining levels of potassium in the artist’s body to the mining of potash from the local area. The work features photographs of the artist’s body inlaid with stones shaped to represent internal organs, such as the thyroid gland. These sculptures are mimetic: there’s an artistic connection between the body and the natural world. They suggest a kind of symbiosis, or reciprocity, between humans and nature.

The work was displayed alongside a painting by Gwen John from the university collection. John, known for her ‘invalid’ paintings, creates a historical dialogue with Dawidek’s exploration of bodily fragility. This engagement with museum collections echoes our critique of the histories of disability, as seen in and Cripping Breath’s archival strand of research. We were inspired, too, by RA Walden’s archive of glass jars containing natural elements such as seeds, leaves, and insects, which Walden uses to explore the way that disability limits access to nature. The jars, reminiscent of specimens found in the Hunterian Museum, evoke medical and museum categorisation systems that have historically been used to pathologise illness and disability.

With Helen, we reflected on how the artists represented in Towards New Worlds cultivate encounters with their artwork: sometimes by playing with access; sometimes via multisensory engagement; sometimes by offering a partial view of subject or text. We venture that these approaches suggest to the viewer the diverse, and potentially disabled, embodiments of other gallery visitors, without necessarily representing disability in direct ways. In Towards New Worlds, we meet a range of artists and their artworks, and through these entry points are brought into relation with other people and perspectives. Louise and Grace, alongside the Artist Collaborators, will continue to think expansively about ways of perceiving art: how we might think of contemporary art as multisensory; and about how this might relate to access, listening, and, as always, breath.

References

Crip Ecologies — RA Walden. (n.d.). Retrieved 3 April 2025, from

MIMA — Towards New Worlds. (2024). MIMA. Retrieved 17 February 2025, from

[Sound of subtitles]. (n.d.). Seo Hye Lee. Retrieved 17 February 2025, from