Literature of the English Country House: Doubles, foils and the houses of 'others' in Great Expectations

In a very special post we are joined by Dr Amber Regis, one of this week’s Educators on the Literature of the English Country House MOOC.

We are used to thinking and writing about literary characters as types. We categorise, give labels and make comparisons. In Aspects of the Novel (1927) E.M. Forster drew the distinction between flat and round characters, between caricatures on the one hand and complex, changing characters on the other.

Forster was interested in how some character types dominate the work of particular writers, and how these types can also appear together on the same page. More generally, literary criticism often speaks of ‘doubles’ and ‘foils’, where the first is a pairing of characters on the basis of similarity, and the second is a pairing on the basis of difference.

When it comes to character we’ve long been in the habit of reading in relation. We trace how characters respond to and interact with others, and we interrogate the meaning of such interaction. But what I’d like to do here is extend this practice to space and place.

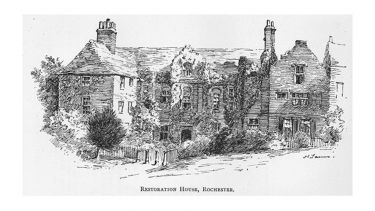

On MOOC this week we’ve been looking at Satis House, the decaying home of Miss Havisham. In what follows, I’d like to explore how Satis House might be read in relation to other homes, houses and buildings in the novel. What do we learn about the country house in Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations if we step outside its grounds?

First, to set the scene, a quick reminder of how Satis House (our ‘main character’ for this exercise) is described in the novel. It is “a large and dismal house barricaded against robbers” located “up town” from Joe Gargery’s forge in the region of the Kent marshes.

Its gates are locked, the main entrance is chained and the windows are barred. The estate brewery remains empty and unproductive, and the courtyard and garden are overgrown. Here Miss Havisham lives alone with Estella, her adopted daughter (though at different times in the novel, Sarah Pocket and Orlick will also occupy this space).

We encounter Miss Havisham in her dressing room and dining room. She continues to wear her half-arranged wedding clothes and the wedding banquet remains on the table, slowly rotting away. Though Satis House is clearly in a state of decay, Miss Havisham attempts to preserve her home as it was at the moment she discovered that Compeyson had left her a jilted bride.

There are lots of potential comparisons to be drawn between Satis House and the houses of others. But here I will limit myself to three buildings. At first glance, all appear to be ‘foils’ — but a closer look makes such neat distinctions increasingly difficult to sustain.

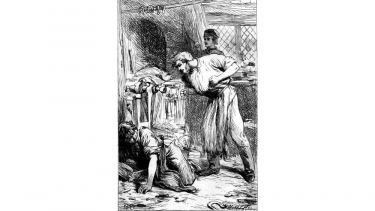

Pip’s home and Joe Gargery’s forge

From Chapter II:

Joe’s forge adjoined our house, which was a wooden house, as many of the dwellings in our country were,—most of them, at that time.

I got up and went down stairs; every board upon the way, and every crack in every board calling after me, ‚ÄúStop thief!‚Äù and ‚ÄúGet up, Mrs. Joe!‚Äù In the pantry, which was far more abundantly supplied than usual, owing to the season, I was very much alarmed by a hare hanging up by the heels, whom I rather thought I caught when my back was half turned, winking. I had no time for verification, no time for selection, no time for anything, for I had no time to spare. I stole some bread, some rind of cheese, about half a jar of mincemeat (which I tied up in my pocket-handkerchief with my last night‚Äôs slice), some brandy from a stone bottle (which I decanted into a glass bottle I had secretly used for making that intoxicating fluid, Spanish-liquorice-water, up in my room: diluting the stone bottle from a jug in the kitchen cupboard), a meat bone with very little on it, and a beautiful round compact pork pie. ∞⁄‚Ķ] There was a door in the kitchen, communicating with the forge; I unlocked and unbolted that door, and got a file from among Joe‚Äôs tools.

There is architectural doubling at work here—the forge adjoins Pip’s wooden home, much like the brewery adjoins Satis House. The first is a productive relationship, with people and the products of labour moving back and forth through “communicating” doors (and look at the relationship between tools and food in the passage above, both of which Pip steals to give to Magwitch).

But the second is an unproductive relationship. There is no longer a head clerk or manager at Satis House brewery, and no beer from its casks is consumed in the main house. Miss Havisham and Estella must consume bought-in food and drink; they are simply consumers, not producers.

In the early chapters of the novel, Pip’s home and Satis House, though different in degree, are also governed by similar powers. Both are subject to the tyranny of a matriarch: Miss Havisham and Mrs Joe (and notice how both are known by their titles, indicating their marital status). Both women exert power—physical in the case of Mrs Joe, who beats Pip to raise him “by hand”; and psychological in the case of Miss Havisham, who manipulates and exploits Pip’s ‘expectations’.

Both women are violently removed from the novel—Mrs Joe is attacked, disabled and later dies, while Miss Havisham never recovers from the burns sustained when her wedding dress catches fire. After the removal of these women, each space undergoes a transformation—the wooden house and forge become a happy family home after Joe’s second marriage to Biddy; and by the end of the novel, Satis House is razed to the ground.

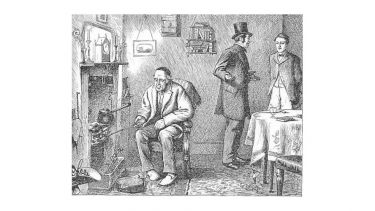

Wemmick’s home — the ‘Castle’ at Walworth

From Chapter XXV:

Wemmick’s house was a little wooden cottage in the midst of plots of garden, and the top of it was cut out and painted like a battery mounted with guns.

“My own doing,” said Wemmick. “Looks pretty; don’t it?”

I highly commended it, I think it was the smallest house I ever saw; with the queerest gothic windows (by far the greater part of them sham), and a gothic door almost too small to get in at.

“That’s a real flagstaff, you see,” said Wemmick, “and on Sundays I run up a real flag. Then look here. After I have crossed this bridge, I hoist it up-so—and cut off the communication.”

The bridge was a plank, and it crossed a chasm about four feet wide and two deep. But it was very pleasant to see the pride with which he hoisted it up and made it fast; smiling as he did so, with a relish and not merely mechanically.

“At nine o’clock every night, Greenwich time,” said Wemmick, “the gun fires. There he is, you see! And when you hear him go, I think you’ll say he’s a Stinger.”

∞⁄‚Ķ]

“I am my own engineer, and my own carpenter, and my own plumber, and my own gardener, and my own Jack of all Trades,” said Wemmick, in acknowledging my compliments.

The interval between that time and supper Wemmick devoted to showing me his collection of curiosities. They were mostly of a felonious character; comprising the pen with which a celebrated forgery had been committed, a distinguished razor or two, some locks of hair, and several manuscript confessions written under condemnation,—upon which Mr. Wemmick set particular value as being, to use his own words, “every one of ’em Lies, sir.”

These were agreeably dispersed among small specimens of china and glass, various neat trifles made by the proprietor of the museum, and some tobacco-stoppers carved by the Aged. They were all displayed in that chamber of the Castle into which I had been first inducted, and which served, not only as the general sitting-room but as the kitchen too, if I might judge from a saucepan on the hob, and a brazen bijou over the fireplace designed for the suspension of a roasting-jack.

Pip befriends Wemmick, who is clerk to Jaggers (the lawyer responsible for administering his ‘expectations’ and giving out his allowance). Wemmick cultivates a public face of cold professionalism which he ‘wears’ at work (caricatured by Dickens in his description of Wemmick’s “post-office” mouth and “mechanical appearance of smiling”), and a private face of affability and hospitality worn at home in Walworth.

This home is a small cottage in a “sham” gothic style, but its windows and doors, moat and drawbridge, flagpole and cannon—the result of Wemmick’s DIY—conceal a warm and welcoming domestic circle of family and friends.

Here there is some imitative doubling of Satis House and Miss Havisham. Both buildings are fortified against the outside world, and both house owners withdraw from the public sphere. Wemmick attempts to leave the world of work behind him at the office, lifting the drawbridge and cutting off all contact with lawyers, clerks and clients. But the Castle’s fortifications are “sham”, and unlike Miss Havisham, Wemmick’s withdrawals from public life are temporary—he makes regular sallies back into the world.

The Castle at Walworth is also full of what Wemmick describes as “portable property”; it contains stuff, objects and things made or used by Wemmick and his father, or collected by Wemmick during working hours.

He is particularly proud of the souvenirs acquired from infamous prisoners and trials, and early in the novel he reflects upon their value: “They’re curiosities. And they’re property. They may not be worth much, but, after all, they’re property and portable. It don’t signify to you [Pip] with your brilliant lookout, but as to myself, my guiding-star always is, ‘Get hold of portable property’.”

Wemmick’s obsession with owning and keeping “portable property” causes him to withdraw his stock of goods from the public sphere. Once acquired, they are removed to Walworth where they accumulate but do not circulate.

Here we are reminded of Miss Havisham’s similarly ‘frozen’ assets: her “bright jewels” and dresses; her “watch and chain”; “handkerchief and gloves”; and her prayer-book and looking-glass. Both Wemmick and Miss Havisham keep rather than use these objects of value.

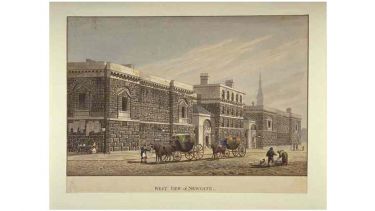

Newgate prison

From Chapter XXXII:

We were at Newgate in a few minutes, and we passed through the lodge where some fetters were hanging up on the bare walls among the prison rules, into the interior of the jail. At that time jails were much neglected, and the period of exaggerated reaction consequent on all public wrongdoing—and which is always its heaviest and longest punishment—was still far off. So felons were not lodged and fed better than soldiers, (to say nothing of paupers,) and seldom set fire to their prisons with the excusable object of improving the flavor of their soup. It was visiting time when Wemmick took me in, and a potman was going his rounds with beer; and the prisoners, behind bars in yards, were buying beer, and talking to friends; and a frowzy, ugly, disorderly, depressing scene it was.

It struck me that Wemmick walked among the prisoners much as a gardener might walk among his plants. This was first put into my head by his seeing a shoot that had come up in the night, and saying, “What, Captain Tom? Are you there? Ah, indeed!” and also, “Is that Black Bill behind the cistern? Why I didn’t look for you these two months; how do you find yourself?” Equally in his stopping at the bars and attending to anxious whisperers,—always singly,—Wemmick with his post-office in an immovable state, looked at them while in conference, as if he were taking particular notice of the advance they had made, since last observed, towards coming out in full blow at their trial.

Staying with Wemmick, let us join him as he tends his “plants” within the walls of Newgate prison. If his dual personality and obsession with accumulating “portable property” has not already made you suspicious, seeing Wemmick as the “gardener” of Newgate most certainly will.

In the scene immediately following this extract, Wemmick receives the gift of a pair of pigeons from a prisoner—and here the reader is reminded of the source of many of those things and objects in his collection at Walworth. Tending these plants in Newgate, Wemmick enjoys the harvest.

But Newgate too is a home of sorts and its barred windows evoke those of Satis House, and like Miss Havisham, its prisoners do not stray beyond the walls that contain them. Wemmick’s visits to Newgate also evoke Pip’s visits to Satis House—both are prison visitors, an increasingly popular activity for philanthropists and reformers during the nineteenth century.

Pip feels the influence of his visits to both Satis House and Newgate. After joining Wemmick on one of his visits, Pip leaves Newgate with the prison “in my breath and on my clothes.” He wishes to rid himself of the association and “beat[s] the prison dust off [his] feet”, “[exhaling] its air from [his] lungs.”

There is an echo here of Pip’s response after his first visit to Miss Havisham. Having been scorned by Estella on account of his clothes and speech—clear markers of social class—Pip travels home from Satis House and reflects upon the “low-lived bad way” of his life at the forge. In both cases, there is an internalised sense of shame brought about by Pip’s encounter with these spaces.

Written by Amber Regis, on 28 July 2015.

View , and .