Online Abuse toward Candidates during the UK General Election 2019

In this blog post I’m going to discuss the 2019 UK general election and the increase in abuse aimed at politicians online.

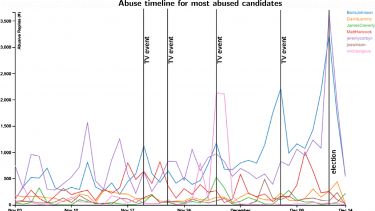

We collected 4.2 million tweets sent to or from election candidates in the six week period spanning from the start of November until shortly after the December 12th election. The graph above shows the who received the most abuse up to and including December 14th, with Boris Johnson and Jeremy Corbyn receiving the most by far.

The 2016 "Brexit" referendum left the parliament and the nation divided. Since then we have seen two general elections, and two Prime Ministers jostle to strengthen their majority and improve their negotiating position with the EU. National feeling has never been so polarised and it will come as no surprise that with the social changes brought about through the rise of social media, abuse towards politicians in the UK has increased. Using natural language processing we can identify abuse and type it according to whether it is political, sexist or simply generic abuse.

Our work investigates a large tweet collection on which natural language processing has been performed in order to identify abusive language, the politicians it is targeted at and the topics in the politician’s original tweet that tend to trigger abusive replies, thus enabling large scale quantitative analysis. A list of slurs, offensive words and potentially sensitive identity markers was used. The slurs list contained 1081 abusive terms or short phrases in British and American English, comprising mostly an extensive collection of insults, racist and homophobic slurs, as well as terms that denigrate a person’s appearance or intelligence, gathered from sources that include http://hatebase.org and Farrell et al [2].

Method

Tweets were collected in real-time using Twitter‚Äôs streaming API. We began immediately to collect any candidate who had been entered into Democracy Club‚Äôs database[10] who had Twitter accounts. We used the API to follow the accounts of all candidates over the campaign period. This means we collected all the tweets sent by each candidate, any replies to those tweets, and any retweets either made by the candidate or of the candidate‚Äôs own tweets. Note that this approach does not collect all tweets which an individual would see in their timeline, as it does not include those in which they are just mentioned. We took this approach as the analysis results are more reliable due to the fact that replies are directed at the politician who authored the tweet, and thus, any abusive language is more likely to be directed at them. Ethics approval was granted to collect the data through application 25371 at the University of ∫˘¬´”∞“µ.

Findings

Table 1 gives overall statistics of research period, which contains a total of 184,014 candidate-authored original tweets, 334,952 retweets and 131,292 replies. 3,541,769 replies to politicians were found, of which abuse was found in 4.46%. The second row gives similar statistics for the 2017 general election period. It is evident that the level of abuse received by political candidates has risen in the intervening two and a half years.

In terms of representation in the sample of election candidates with Twitter accounts, gender balance is skewed heavily in favour of men for the Conservatives and LibDems; Labour in contrast had more female/non-binary than male candidates. Most abuse is aimed at Jeremy Corbyn and Boris Johnson, with Matthew Hancock, Jacob Rees-Mogg, Jo Swinson, Michael Gove, David Lammy and James Cleverly also receiving substantial abuse. Michael Gove received a great deal of personal abuse following the climate debate. Jo Swinson received the most sexist abuse.

| Period | Original MP tweets | MP retweets | MP

replies |

Replies to MPs | Abusive replies to MPs | %

Abuse |

| 3 Nov–15 Dec 2019 | 184,014 | 334,952 | 131,292 | 3,541,769 | 157,844 | 4.46 |

| 29 Apr–9 Jun 2017 | 126,216 | 245,518 | 71,598 | 961,413 | 31,454 | 3.27 |

Who is getting abuse?

The topic of Brexit draws abuse for all three parties. Conservative candidates initially move away from this, toward their safer topic of taxation, before returning to Brexit. Liberal Democrats continue to focus on Brexit despite receiving abuse. Labour candidates consistently don’t focus on Brexit; public health is a safe topic for Labour.

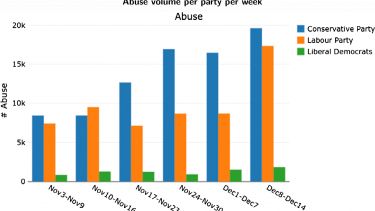

Levels of abuse increased in the run up to the election. The figure below highlights the number of abusive tweets received by the three major parties. There is a considerable spike for both Labour and the Conservatives in the week prior to the election.

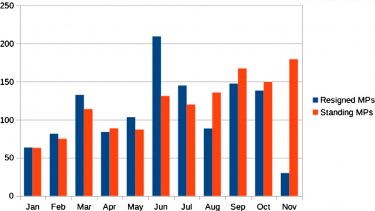

In the graph below we look at the average abuse per month received by MPs did not stand again those who did choose to stand again. We see that in all bar one of the earlier months of the year those individuals received more abuse, and particularly in June.MPs who stood down received more abuse than those who chose to stand again in all but one month in the first half of 2019, and in June they received over 50% more abuse.

Conclusions

Between Nov 3rd and December 15th, we found 157,844 abusive replies to candidates’ tweets (4.44% of all replies received)–a low estimate of probably around half of the actual abusive tweets. Overall, abuse levels climbed week on week in November and early December, as the election campaign progressed, from 17,854 in the first week to 41,421 in the week of the December 12th election. The escalation in abuse was toward Conservative candidates specifically, with abuse levels towards candidates from the other two main parties remaining stable week on week; however, after Labour’s decisive defeat, their candidates were subjected to a spike in abuse. Abuse levels are not constant; abuse is triggered by external events (e.g. leadership debates) or controversial tweets by the candidates. Abuse levels have also been approximately climbing month on month over the year, and in November were more than double by volume compared with January.

[1]

[2]